Georg Buchner’s early 19th century play is often heralded as one of the greatest in European theatre, and yet, horrible dictu, many seasoned theatregoers (myself included) have never heard of either the playwright or his magnum opus before. An ostensibly much-neglected, elusive classic, this London production is the world premiere of a new (apparently very free adaptation) by acclaimed playwright Jack Thorne (who brought Harry Potter (review) to the stage).

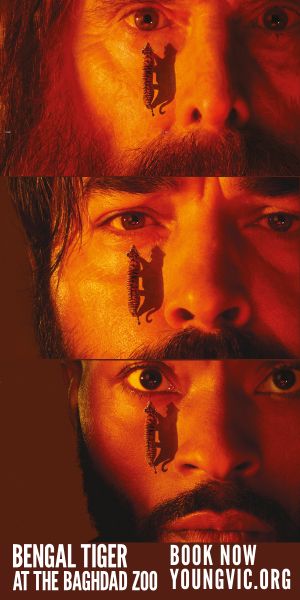

Powerfully updated to 1980s Berlin, the play is set against the backdrop of the Cold War, where a young British squaddie, Frank (John Boyega), living in insalubrious conditions above a halal abattoir with his Irish Catholic partner and their baby daughter, urgently needs money to help provide for his struggling family.

John Boyega as the eponymous protagonist acquits himself admirably and the physicality of the role is no barrier to his performance.

Emotionally damaged in childhood by abandonment by his mother – it is a profoundly Oedipal play – and a traumatic incident sustained whilst on a previous tour of duty in Belfast, Frank enlists in a medical trial in return for money, popping pills which seemingly precipitate his tortuous decent into ugly paranoia and murderous madness.

At its heart, the play is a study of acute psychological disintegration, loss of sanity and a profoundly dark mediation on the nature and consequences of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). It is also a damning indictment of how the army – and people at large – blithely treat sufferers of PTSD, and mental illness in general.

As we watch the male, working class psyche painfully disintegrating, blurring fantasy and reality into a dystopian present, we the audience are even ourselves unsure of the truth.

Romantic love, and the effects of poverty on it, toxic masculinity, lust, infidelity and insecurity, jealousy, religion and a sense of belonging are all themes which Woyzeck explores, some more successfully than others.

To his credit, Boyega as the eponymous protagonist acquits himself admirably. The physicality of the role is no barrier to his performance, and his celluloid, Jedi-inspired one dimensionality is thankfully cast aside to reveal poignant nuances of emotion hitherto unseen. His choice of an unconventional, sinister and challenging role must also be applauded, given his clean cut, Hollywood star branding.

Aesthetically, Woyzeck is captivating and rewarding. The stunningly simple yet ruthlessly effective minimalist set – the Berlin Wall, daubed in open, bloody wounds, symbolic of Frank’s emotional trauma, the eerie, pulsating, trance-like music and the harsh, atmospheric lighting are all superbly realised.

Nancy Carroll is captivating as the calculating, Circean, unfaithful general’s wife. The animalistic sexual coupling between her and Andrews (Frank’s best friend, played with electrifying, raucous Northern humour by Ben Batt) is beautifully, albeit predictably choreographed.

Directed with laudable aplomb and brio by Joe Murphy, Woyzeck is an exceedingly sombre, powerfully stylised yet ultimately emotionally unfulfilling production. At its best, this Old Vic offering is audacious and occasionally funny, but fails in its attempt to rise above the pedestrian by its repeated efforts to be shocking.

Aesthetically, Woyzeck is captivating and rewarding. The stunningly simple yet ruthlessly effective minimalist set – the Berlin Wall, daubed in open, bloody wounds, symbolic of Frank’s emotional trauma, the eerie, pulsating, trance-like music and the harsh, atmospheric lighting are all superbly realised.

Yet as a production, it suffers from its tawdry attempts at titillation, with gratuitous full-frontal nudity (which detracts from the integrity and veracity of the piece) and crass, expletive-laden humour both punctuating the play.

With conscious overtones of Othello and the Moor’s malevolent sexual jealousy, and with the enormity of Woyzeck’s insanity becoming readily apparent, the tragic denouement is both somewhat predictable and memorable for the wrong reasons.

British audiences will no doubt be won over by the calibre of the performances, and may leave the theatre saddened by the genuine pathos of the tragedy they have witnessed, but at the same time may well remain emotionally unconvinced by this Germanic proletarian tale of love, loss and psychological damage.