There are some theatre shows that seem so ‘complete’ – so integrated – that each component of the production’s ‘world’ appears inextricably linked; each moment of ‘magic’ seeming to dovetail with another (again and again), until one simply surrenders to the experience and allows the show to ‘show you’ (a bit like life, really).

Put simply, The Ocean at the End of the Lane, is as seamless a piece of theatre as I’ve experienced in a long time. Indeed, the enjoyment was magnified because, just as theatre is the adult world’s attempt to harness the short-lived, random, chaotic ‘magic’ of childhood (and its attendant memories), so too does this production. Indeed, in what might be described as ‘prologue’, the adult protagonist is invited by Old Mrs Hempstock (deliciously played by the fabulously-named Penny Layden) to retrace his childhood footsteps, (literally) hauls his (hitherto unseen) younger ’10-year-old’ self from the orchestra pit (of memory), up onto the live stage to retrace his journey.

It seems equally rare to experience – either during the interval, or when executing the ‘post-show shuffle’ towards the exit – universally positive engagement towards a show.

As a result, a middle-aged man weighted down by his newly-deceased father’s wake, is transformed into a ’10-year-old ‘boy’, so as to investigate his one-time childhood ‘haunt’, a country farm near his familial home, replete with pond (the titular ‘ocean at the end of the lane’).

The 10-year-old ‘Boy’ is played by James Bamford with a similar heightened energy as has been witnessed in the National Theatre production The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night Time In that instance, the protagonist was a young man ‘on the spectrum’. This consistent central performance certainly binds everything, and he is to be commended for it.

After ‘Boy’ witnesses the shocking aftermath of one-time lodger’s suicide, we are soon introduced to ‘Dad’ (Nicholas Tennant in a moving, subtly transmuting dual-performance), and to younger sibling ‘Sis’ (portrayed as irritating ‘precious princess’ archetype by Grace Hogg-Robinson). The subtext is that the siblings’ mother has died recently, making the story – as was well as Tennant’s performance – even more multi-layered.

After meeting the heavily foreshadowed ‘childhood friend’ Lettie Hempstock (a sensational Nia Towle on her professional debut), the story moves swiftly from one ‘memory’ / dramatic sequence to another; no sooner has one childhood preoccupation / trauma / catastrophe been dealt with, then another one arrives to supplant it.

Laura Roger’s Norma Desmond-esque portrayal of Dad’s ‘companion’ Ursula (AKA chief flea, Skarthach) could – with less subtlety – have been a little too ‘on the nose’; that it works so well is because those who created it – believe in it, and wish us to do the same.

This is a brilliant reminder of how the magic of great theatre can heal, as well as help to mitigate the setting aside of cherished childhood preoccupations

The story is based on a novel by Neil Gaiman; with adaptation by Joel Horwood. It is very well realised, with seemingly each line being used to convey the magic that only childhood can convey, horrors beyond its understanding, or the elusive memories that exist in-between.

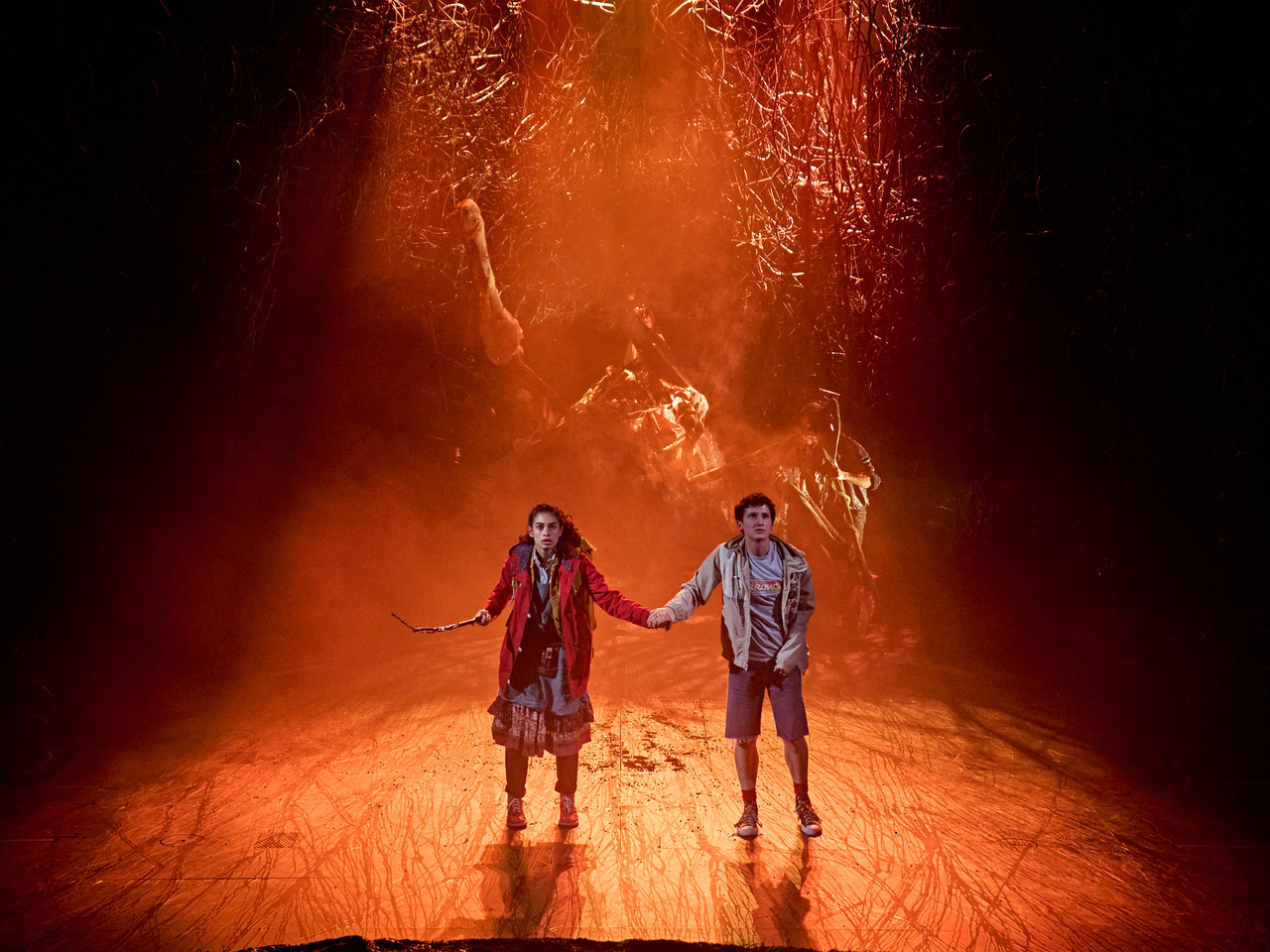

In this respect, most every theatrical trick ‘outside the book’ is utilised to realise the premise: dance, puppetry, sound, lighting, wirework, ensemble movement, as well as some of the best integration of prop and set ‘business’ I’ve seen in a stage production.

From the root to the fruit, this show is… simply brilliant.

The production, under Katy Rudd’s brilliant direction is very self-aware; however, as each emotional ‘beat’, set-piece or sequence is treated with the same deftness of touch and reverence (‘hold on tightly, let go lightly’), it neither falls into pomposity, nor drifts aimlessly into pantomime. Whichever of the theatre world’s common tropes is being alluded to – whether horror, suspense, comedy of manners, Peter Pan, Grimm fairytales, close-up magic or even Michael Jackson’s ‘Thriller’ video – a remarkable sense of taste, conviction, clarity and fluidity is on display; a result only possible if all components are working well together (take a bow all within the National Theatre who made this possible).

This is a brilliant reminder of how the magic of great theatre can heal, as well as help to mitigate the setting aside of cherished childhood preoccupations.

Despite – presumably – most of the attendees having a predisposition towards the behavioural norms and (potential) transformative rewards of theatre, for most their choice of a ‘diverting night at the theatre’ is not ‘do-or-die’; as a result, true immersion is rare. Indeed, it seems equally rare to experience – either during the interval, or when executing the ‘post-show shuffle’ towards the exit – universally positive, focused engagement towards a show.