In early 1917, during thick fog, SS Mendi – having set sail from Cape Town with a cargo including hundreds of black South African volunteers bound for France to dig trenches for Allied Forces – was hit, and sunk, 13 miles off the Isle of Wight by a larger cargo ship.

An achingly beautiful piece

Six hundred and sixteen South Africans and 30 of the ship’s crew drowned that day. The cargo ship – on the orders of the captain – sailed away, rather than help the doomed South Africans. The captain was charged and found guilty of malpractice and was sentenced to 12 months… suspension of his seafaring license.

This opera – the second production in South African theatre company Isango Theatre Company’s touring programme to Royal Opera House’s Linbury Theatre – is not just a dramatisation of a little-known First World War maritime ‘disaster’; it is a clear-sighted examination of race-based injustice, and a soulful exploration of colonial expediency – from the point of view of those deemed most expendable.

In terms of set-design, musical orchestration and creative direction, this piece follows a similar path to the company’s sister show, A Man of Good Hope (read review).

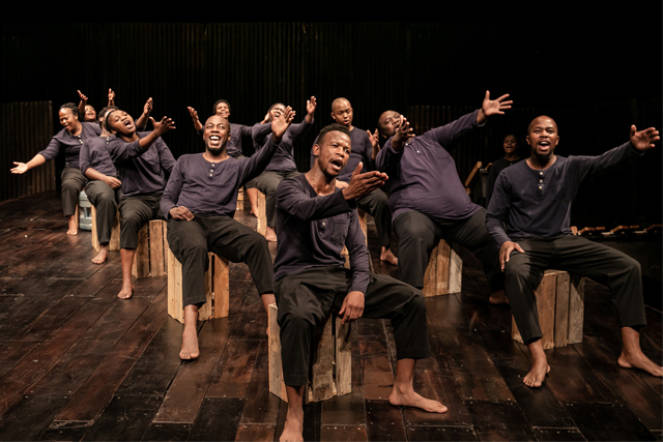

The staging is stripped back, with only corrugated iron strips on the back and sides of the bare stage. Devoid of props – save for empty boxes (seats), sticks (whips), black cloths (shrouds), rope (sides of the ship), and shovels brought on and off by the cast – the raked stage is set for the performers to tell the story.

Narratively, it takes its story (and travellers) away from mainland Africa, and – with eyes pointed towards colonisers and subjugators alike – sets sail for recognition, if not justice.

The tale is told in chronological order. It starts with a recruitment drive, wherein local South Africans are asked to volunteer in the ‘fight against the Germans’ in order to ‘help preserve democracy’. Using financial incentives – an important element for a people whose traditional ways of life and means of subsistence had been so recently dismantled by foreign interlopers – members of various tribes and clans are persuaded into the employ of Her Majesty’s Army…as ditch diggers.

The training regime is dealt with cleverly; Anglo-centric military songs such as ‘It’s a long way to Tipperary’, and traditional Christian hymns (‘How great thou art’) are performed excellently, using marimbas and various percussion instruments placed on either side of the stage. The juxtaposition of these songs – aural embodiments of ‘Britishness’ – being performed with such gusto and style by those the ‘mother country’ ultimately viewed and treated as second-class (“monkeys”), is especially poignant.

Just as strikingly, during both the training and the voyage, we see traditional tribal enmities and disagreements settled for the common good. However, there is one particularly tragic story line depicted (prior to the final calamity) which suggests that not all African traditions/beliefs systems travelled well.

Each and every one in the Isango Ensemble leaves their mark, as does this show

With that being said, there are many allusions to – and reminders of – ship-life during the earlier (and longer) voyages from Africa, at the time of the Trans Atlantic Slave Trade; not just in relation to the fact that the cargoes were made up of Black Africans, but in respect to the countless proud souls who lost their identities, lives, and individual legacies (even after death) as a result.

Many instances of loss, grief, resentment and pain – mixed with pride, strength, empathy, compassion, cooperation and comradeship – are explored here; not only through the superb acting and concise dialogue but, just as strikingly, by the soulful South African music.

Two powerful musical moments (of many) are expressed a) by two females left behind, singing a harmonized farewell lament to those setting sail (a beautiful waltz-time duet), and b) when – following a particularly brutal on-board disciplining exercise – we experience an incredibly powerful choral ‘African blues’.

By the time the beautifully staged denouement arrives– and the eponymous dance of the ‘forgotten dead’ is performed (to mainly drum accompaniment) – sounds and images far beyond those depicted on stage are evoked.

Music – directed by Mandisi Dyantyis and Pauline Malefane – is not only poignant and evocative, but beautifully performed and sung, while Mark Dornford-May’s direction is sure-handed, yet compassionate.

It would be unfair to further single out any performer, practitioner or producer; suffice to say that each and every one in the Isango Ensemble leaves their mark, as does this show.

This is an achingly beautiful piece – go and see it.