The ‘arc’ generally refers to an emotional, physical, situational and or spiritual journey undertaken by a character through the course of a theatre play, film, radio or TV series. With this in mind, the point of Arinzé Kene’s play could not be clearer.

The beauty of Kene’s writing is that he constantly strives to bridge the gap between the personal and impersonal

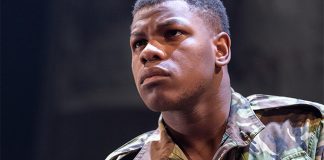

With only a large wooden cube as a set – and an old bicycle briefly used as a prop – writer Kene’s onstage avatar ‘Boy’ (Kwaku Mills) grows up in front of our eyes. Through a series of monologues – and a steady procession of pre-recorded voice-overs – the black teenage schoolboy of African descent growing up in ‘80s England, presents his view on the various characters from within his urban community.

The cast of [unseen] characters includes: a disaffected Indian shopkeeper (‘Gandhi’) and his stray cat; an estranged middle-aged black couple (the Blackwoods); a cricket-loving father and son (both named Trevor’); an unidentified ghost (‘Duppy’); an itinerant street-dweller (‘Old Man Bolton’); and two local dogs (one a large bully, the other, small and timid).

This doesn’t even include the list of people more directly linked to our protagonist: his absent – yet ever-present – father; a (barely managing) mother; a best friend/girlfriend (‘Jamelia’); a succession of female spectators, both old (‘what, what girls’) and new (‘nah, nah girls’); and two male bullies (‘Desmond’ and ‘Massive Martin’).

When we first meet ‘Boy’, he is an awkward teenager, still trying to make the transition from the idealised preoccupations and studied naivety of youth, to the often mundane – and sometimes harsh – realities of ‘grown-up’ living. As he outlines his own battles with dyslexia, parental absence and broken promises, and school-yard beatings – and relates to various other community members coping with infidelity, poverty, disappointing life choices…death (!) – he becomes more battle-hardened, world-weary…cynical.

One of the play’s most powerful moments is when – after taking a particularly vicious beating – he turns his back on his father’s advice to ‘always be good’. Up to that point, his world-view had been shaped by this advice; his childhood disappointments, depravations and injustices assuaged by these comforting words. During the assault, however, he has an epiphany and, thereafter, chooses to give in to the chaos. As a result, instead of merely observing and documenting the harsh realities of the outside world, he blends right in.

In the denouement, there is hope that a ‘phoenix might ascend from the ashes’. By this point, the planned-for ‘pyrrhic victory’ has come at a huge cost; whether it’s too high depends – as everything does – on one’s point of view.

Mills’ portrayal of this ‘death of innocence’ – a gradual series of physical and verbal transitions, rather than a sudden metamorphosis – is focused, nuanced and well calibrated.

The piece is funny and tragic, often at the same time

Of course, he is helped by the writing, and by Natalie Ibu’s forensic direction. Amelia Jane Hankin’s set design is both spare and practical, the translucent cube representing everything from high-rise flats, garden fencing…even a burning building. As well as a structure to climb and traverse, it offers Boy some much-needed support, and symbolises (perhaps) the only tangible ‘character’ he can truly lean on.

Helen Skierra’s sound design and Zoe Spurr’s lighting design are also instrumental in building the scene(s); the voice-overs, sound-layering, and lighting each lending weight – and corroboration – to the stories (and voices) in Boy’s head.

The piece is funny and tragic, often at the same time. There are several moments where one is reminded of just how ‘tabloid’ – how throwaway – other people’s struggles can appear to be when viewed from a ‘safe’ distance.

The beauty of Kene’s writing is that he constantly strives to bridge the gap between the personal and impersonal, and to remind us how difficult it is to commit to the lives of others without fully committing to our own.