We live in interesting times.

In Britain, there are laws that, not only deny the right to peaceful protest for the masses, but effectively criminalise the public’s right to free assembly, should the offending group be arbitrarily deemed a nuisance (by a police figure, or member of the judicial/ political establishment).

When we factor in the UK government’s recent employment of unethical district-gerrymander

“The entire cast deserves respect”.

Meanwhile… the political right wing in the US has lost significant ground in the ‘culture war’ arguments to the triple threat of empathy, progressive thought and ‘non-White immigration – has also decided to ‘simplify’ its quest for power by reducing the general public’s influence at the ballot box.

They do this by literally – and habitually – lying to the public (through paid ads and media interviews), engaging in underhand voter subversion, employing more direct insurrectionist methods, or simply using its radical Right-wing majority in the Supreme Court to dissemble and dismantle those guard-rails, protections, safeguards and/or enabling mechanisms designed to bridge the gaps between diverse, poor or underprivileged communities and the rich elite; whilst simultaneously, amping up the fear-factor by demonising ‘the other’, and diluting/removing all gun-control laws.

Ultimately, the escalation of such patently ‘anti-democratic’, immoral and discriminatory methods by certain elites within these two nations is simply to draw attention from established practices of self-enrichment, at the expense of the general public.

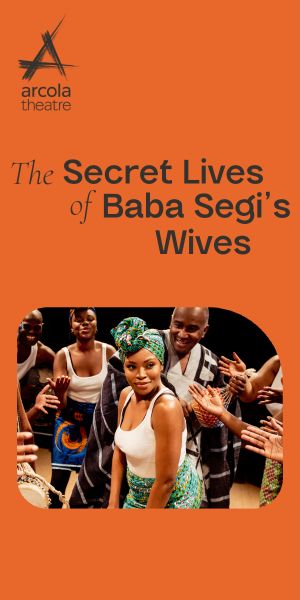

‘What has this got to do with a play based almost entirely in one location in Nigeria, West Africa?’, one might well ask. The answer lies in playwright Kwame Kwei-Armah’s clever – almost Tarantino-esque – use of dialogue, chronology-defying ‘sleight-

The play’s first act starts with Beneatha (Cherrelle Skeete) making an impassioned speech during a mid ’60’s student campus riot in the United States; it ends with her preparing to make the journey.

“Kwame Kwei Armah deserves huge applause for creating a piece that draws so heavily from the past while embracing both the current zeitgeist, and pointing a way to a positive future”.

In between, we are shown – in one long scene – the circumstances that shape the play’s narrative, and her entire life.

The main thrust of act one deals with Beneatha and her new husband Joseph Asagai (Zackary Momoh) – having travelled from the US to Nigeria to further his political career, and to establish local independence in the face of UK/US colonisation – moving into their new home in Nigeria in 1959.

Having met when he was teaching at a US university in which she was studying, it soon becomes clear that theirs is a love based on mutual respect, intellect and a shared destiny.

There is both food for thought and much amusement to be had from the dialogue, as they are met by – respectively – iterations of ‘the past’ (previous owners ‘the Nelsons’), present (‘Aunty Fola’) and future (neighbour Daniel Barnes).

Despite the funny dialogue and fish-out-of-water tropes, the stakes soon grow higher as we hear news of pregnancy, toxic politicking and portents of doom; all garnered amidst posters, statues and masks evoking ‘mammies and coonery’.

Once we get to the rug-pulling end of the first act, it is easy to imagine the second act’s trajectory; it might be surprising to many.

Without giving away too much, it is fair to say that – as the piece develops, and all in the ensemble save for Cherrelle Skeete portray different characters – the play takes on all the attributes of an ‘intervention’; digging, as it does, into the underbelly of White privilege, toxic masculinity, cultural appropriation, female subservience and patriarchal dominance in a diverse West.

The entire cast deserves respect; especially Zackary Momoh in his twin roles as ‘Wale Oguns’ and ‘Joseph Asagai’. It is Cherrelle Skeete, however, who is extraordinary in portraying every aspect of a multi-faceted character: powerful, vulnerable, caustic, empathetic, vengeful, forgiving, optimistic, and pragmatic.

Based on this performance alone, it is clear that – with similar quality material to choose from – the world is her oyster.

Bearing this in mind, Kwame Kwei Armah deserves a huge applause for creating a piece that draws so heavily from the past while embracing both the current zeitgeist, and pointing a way to a positive future.

The set is simple but effective; while the assorted race-based paraphernalia is both well-researched and oddly emblematic of the modern human condition.

There is much I could quote – or sign-post – in respect to this play. Much of the piece’s content is hinted at by this review’s opening salvos.

Ultimately, I believe, that Kwame Kwei-Armah’s work deserves to speak for itself.

Go and see it.