Sometimes one attends the theatre to have seldom-explored psychic wounds opened up and (re) examined; sometimes one goes to a production to have the same wound(s) balmed and (re) dressed. Oftentimes one is unaware of just what, where, or how deep the lesions are until a good theatrical piece reveals them.

Most productions are designed, constructed and performed to (a) dress these abrasions: to be sufficiently challenging to make an audience feel as if they ‘haven’t seen it all before’, yet familiar enough in concept, performance and execution so as not to either alienate, or bore them unduly.

The cast, direction, sound, music, and lighting are all superb, and this is certainly a very impressive National Theatre production

An Octoroon exists somewhere outside of this basic premise. Of course, it uses many standard theatrical concepts and conceits – often in most ingenious ways – but ultimately it is a theatre piece specifically designed, one feels, to be both entertaining and infuriating in equal measure. As one of the characters says near the end, in its umpteenth ‘4th-wall breaking’ moment: The whole point of this thing was to make you feel something.’

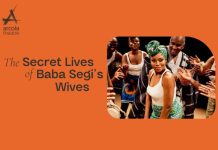

Entering the stage wearing nothing but boxers and socks, the writer Branden Jacob-Jenkins’ representative-on-stage, BJJ (Ken Nwosu) tells the audience of his ‘conversations about race’, with his therapist.

He goes onto talk about the complexity of writing on the topic (‘Do I s*** where I starve?’), and about his admiration for the 19th century playwright, Dion Boucicault, the writer of plantation play, ‘The Octoroon’ – all while listening to overtly sex-based / misogynistic Hip-Hop music, downing a (presumably) alcoholic bottle ‘in one’, and applying ‘white-face’ make-up.

Thereafter, another actor, representing Boucicault himself, enters and – after a brief expletive-filled duologue and extensive strobe effects – we get to see large parts of the aforementioned original play.

From this point on, things go from the sublime to the ridiculous…often and repeatedly.

Most things theatrical – including mime, actors playing multiple roles, acrobatics, numerous knowing asides, live theatre renovations, arson, and even a projected depiction of a famously photographed 20th century lynching – are utilised, in order to ‘make us feel something’.

However, the play’s biggest strength (a surfeit of ideas, theatrical self-awareness) becomes, at times, its biggest weakness.

When a play uses the ‘play-within-a-production’ format to dramatise racial tensions and unease, whilst using a 19th-century slavery narrative, and employing fourth-wall breaking Brechtian conceits to satirise these events, the questions need to be asked: ‘Who – or what – is this for?’

Of course, the cast, direction, sound, music, and lighting are all superb, and this is certainly a very impressive National Theatre production. And yey…

Whilst admiring many aspects of the piece, I found myself more than a little troubled watching a play about plantation living in pre-Civil War America’s Deep South – with its attendant de-humanising language and behavior – being performed by a multi-ethnic cast wearing ‘black-face’, ‘white-face’, and ‘red-face’ alongside a predominantly Caucasian audience. As the piece progressed it felt as if having racist tropes and caricatures constantly lampooned so mercilessly, albeit oftentimes amusingly, felt increasingly reductive.

inventive, witty, literate, well constructed, and worthy of prolonged discussion

Of course I understand that, as a black British man / theatre-goer of a certain age, if I were not to feel somewhat uncomfortable watching aspects of this piece, then either the production would not have been doing its job, or I would not be worthy of my seat in the theatre.

And perhaps that’s the point. After all, with great unease are estuaries formed through which fresh ideas flow to the Sea of Learning.

Perhaps I am not the audience it’s meant for. I am aware that, as a black man, my coped-with ‘discomfort’ within society is an often unspoken – and legislated-for state (“Let it go”, as one character says near the play’s end).

Having said that, seeing and hearing yet more depictions of ‘plantation politics’ – however satirically rendered – does not feel particularly progressive to me.

But perhaps this play – with all its knowingly theatrical tropes and ideas – is meant for ‘other’ theatregoers?

Yes, the term ‘octoroon’ – and elements of the play itself – do flag up ideas of racial identity, and what it means to be unable to walk comfortably on either side of the so-called ‘black/white divide’. However, I would prefer to see more contemporary testimonies on this subject, rather than constantly harking back to safer (if not more mellow) dramatic backdrops.

This play has garnered much discussion, and is certainly a hit with many critics. It is inventive, witty, literate, well constructed, and worthy of prolonged discussion. Ultimately, the writer Brandon Jacob-Jenkins’ talent and inventiveness are clear to see/hear; indeed, so are his American roots.

At a time when black British theatre audiences should be nurtured and encouraged to attend more examples of their own artistic expression/histories – as opposed to yet another representation (albeit a highly inventive one) of a very specific topic / location in black History – is this particular play to be so universally lauded?

I’m not so sure.