J’Ouvert is Yasmin Joseph’s debut play. We caught up with the playwright during rehearsals in sunny South London. Despite the upheaval of cast changes (injury related), a week before opening, Yasmin is upbeat and positive about bringing this production to life. Rightly so, as Yasmin is one of Theatre503’s resident playwrights, The 503Five and her debut play ‘J’Ouvert’ was selected from over 450 submissions. It’s playing now until June 22.

Sophia A Jackson (SAJ): J’Ouvert is your debut play. Can you give Afridiziak readers some background on your journey as a playwright?

Yasmin Joseph (YJ): I went to university and studied English and Drama. I used to perform and throughout the course of my degree I lost my love of performing because of how it was graded. Then I became more invested in finding stories about my experience and things I’m interested in. I gradually started to pull back from performance and started writing. I graduated not necessarily knowing what aspect of theatre I wanted to work in but worked my way around lots of different organisations and I found that I was hiding myself as a writer. I wanted to write but just didn’t know if I could.

I joined the Soho Theatre Young Writers’ Lab and that was amazing. It was the first time I was treated as a writer and was a chance to get stuck into a story. That story (Pinch) was long listed for the Alfred Fagon Award (in 2015) which showed me that story can exist out of my head and in the real world and that story meant something to someone other than myself, so that was exciting. I went away to New York for a year and did an internship at New York Theatre Workshop. They to this series called Mondays @ 3, which meant every week being immersed in a new play and this got me really excited about wanting to write my own stories.

It was a cool experience and I learned a lot about how to approach new writing. I came back and applied for the Theatre503 scheme and pitched this idea. It was literally just a paragraph when I pitched it about what this play could be. It then went from the paragraph to a sample of my writing and I was 100 per cent sure I wouldn’t get it. I nearly didn’t go for the interview because I thought, ‘There’s no point’. Joining Theatre503 has been the most transformative part of being a writer for me as it’s given me the space creatively, to just grow and take an idea from a seed and watch it grow into a full production. Not that many writers get to do that, that quickly.

Joining Theatre503 has been the most transformative part of being a writer for me as it’s given me the space creatively, to just grow and take an idea from a seed and watch it grow into a full production

SAJ: Tell us about being Theatre503’s resident playwright. What does that entail?

YJ: There are five of us. What’s nice about this scheme is that it’s as much about us working collaboratively as it is about us developing our own ideas. We’ve all pitched different plays and it’s about us understanding our process as writers. Every month we have different artists come in and speak to us and they talk to us about their experiences in the industry, their work, their approach to their writing. Throughout that process, we’ve inherited lots of different things. We met debbie tucker green, Roy Williams and he told us how many hours a week he spends writing and how he starts a play. We met Alice Birch, too. The biggest step for me as a writer was prior to the residency I had a habit of writing an idea and keeping it close to my chest (clutches chest) and I found it hard to release them and give them life outside my room.

The artistic director, Lisa Spirling, spotted that early and just ripped the rug from beneath my feet. In the second week of my residency, she encouraged me, made me write a rapid response. This is an initiative they do where writers are invited to the first couple of previews and write a ten-minute response and then it’s peformed two weeks later. It’s a quick turnaround where an idea can’t sit on your shelf. It has to come alive. That was good and got me to a place where I was able to get things on their feet. I learned a lot about how to take notes, as well – what is useful, what needs to get left behind and through the process of redrafting and development, getting a better understanding of my voice and the stories I wanted to tell and making sure that sat in my core as I continued to write the play. With this play, carnival was such a big place, and encompasses so many ideas and so many people have a stake in carnival but because they are so excited by the possibilities of that before you know it, you can get swayed in 50 different directions. It’s not the play of carnival, it’s a play set in carnival. It was great to be held by the theatre throughout that process.

SAJ: I imagine that must be quite a luxury…

YJ: Yeh! When I talk to other writers and they tell me how hard it is just to get their work read… Chasing someone about an email they sent maybe six months ago… I think about the fact that we have such great minds at our disposal.

SAJ: How long did it take to write J’Ouvert?

YJ: Well, you write the pitch, and you have 18 months to write it and then they pay you for two drafts. I was writing up until recently. It’s been about two years but not writing tirelessly for two years. I’d write it. Put it down. Write other stuff and then just get on with life. We’ve done three rounds of research and development and workshopped a few drafts and self-funded at the theatre in March before we did the show.

SAJ: We touched on not being swayed by everyone else’s opinions but how precious are you now that you’re in rehearsals?

YJ: When you are writing the thing, you have to listen to your voice – otherwise the end product isn’t going to be a strong enough basis for you to invite other people to be collaborative because it’s not going to be you. I wanted to make sure that what I bought to rehearsals was the story I wanted to tell. Once you get into the rehearsal room, you become way more aware that this is a shared vision. Hearing about the play from other people and hearing about how existed through their minds and through their eyes, is what breathes life into it, otherwise it’s just me and my play in my room, hunched over a laptop – freaking out.

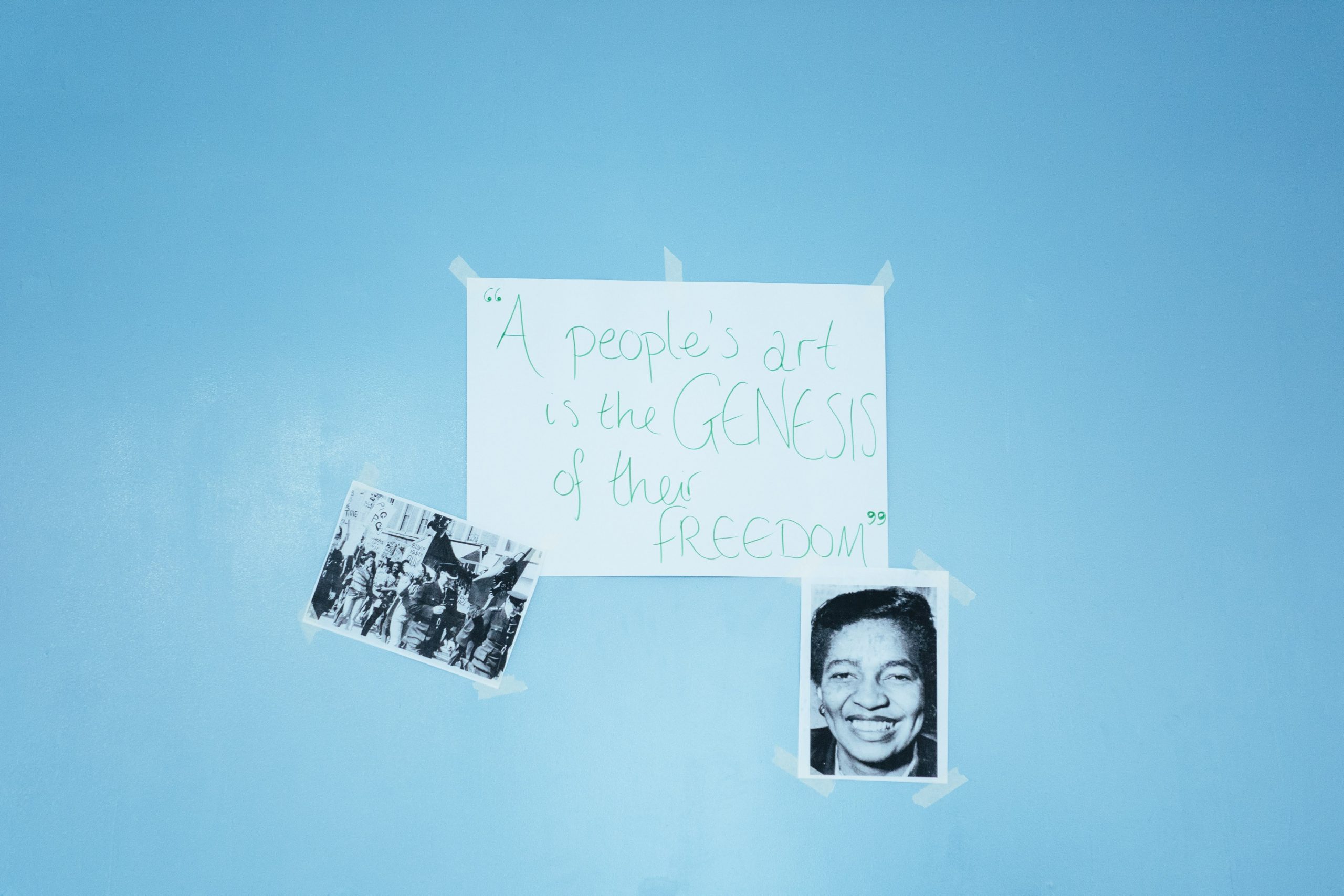

It’s such a big part of my life but I feel that a lot of people who celebrate carnival, and I’m guilty of it myself, forget where carnival comes from and forget what’s at the core of it. Why it happens and why it’s vital and why we should hold on to it for dear life and respect it.

Rehearsals. copyright: Helen Murray

What’s been great about working with Rebekah (director) is that she’s held it like it’s her own, too – which is nice. She tells me things about my play that I don’t know, and I make discoveries. And working with actors, any good actors, they’re going to be inquisitive, they’re going to interrogate your character. Throughout the process, we’ve tried to be as collaborative as possible. We’ve done some cuts, and that’s been kinda hard. Cuts are hard.

The play is funny, so when you’ve got a joke that you love but it doesn’t serve the narrative, you think, ‘that joke bangs, nah, we gotta keep it’, and everyone else is like, ‘nah it’s gotta go’. It’s like that saying that I hate ‘kill your darlings’ – but the scene was smoother and made more sense so it had to go. We also have the limitations of a three-week rehearsal process so we did reach a point where we were more invested in answering questions and had to put a lid on it. It wasn’t stopping other people from offering things as that’s going to happen even through previews, but we reached a point where we felt that we’ve found the version of it that we were going to do for this production.

SAJ: For readers who might be unfamiliar with the term J’Ouvert; what does it mean?

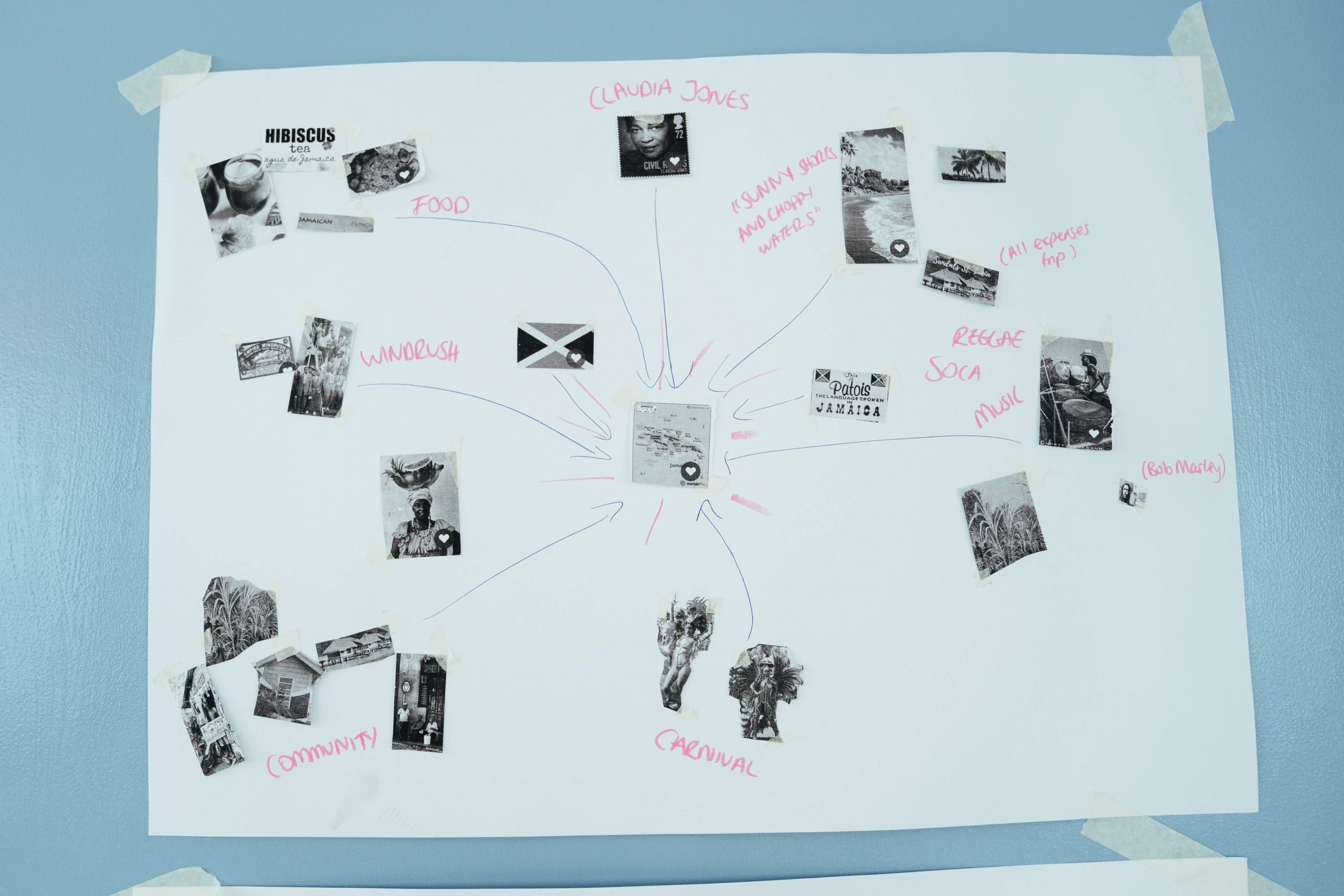

YJ: It’s a Caribbean tradition and it means the beginning of carnival. It’s almost ritualistic. It’s often celebrated by people covering their bodies in oil, chocolate and powder and different substances. There’s something about the anonymity of that experience and everyone being equalised as their bodies and faces are covered and obscured. It just means that people can express themselves in a way that is free of inhibitions and very cathartic and in this play, we use J’Ouvert as a metaphor as an entry to carnival, so it’s the ritual of starting carnival. You get through J’Ouvert and you get to the glory of pretty mas and feathers and your crown.

SAJ: Have you participated in J’Ouvert?

YJ: I have. Prior to writing the play, I was the one saying, I’m not walking around Notting Hill Carnival feeling sticky all day. I’m an avid carnival goer. I don’t necessarily go and do the dutty mas on the Sunday but I did play with Chocolate Nation last year and played mas with my sister and I used to as a child.

SAJ: What inspired you to write J’Ouvert?

YJ: I moved to New York for my internship and I didn’t know anyone there. My first night when I moved there, it was the night before the Labour Day Parade. I was staying with a family friend and I was unpacking, and I could hear Soca music outside and I thought ‘cool, I must be at home, to some extent’. Just hearing that music and seeing my culture and seeing myself in it, I felt this is home, I’ve found a little bit of home, here – even if it’s just for one night. I felt safe enough to go out and explore and have a good time. I went on my own to J’Ouvert in the evening and the next day I went to the parade. I told colleagues and friends where I’d been, and they looked at me like I was absolutely insane. I couldn’t work out why and they were like ‘it’s really dangerous’.

Then the next year I came home, and I read the story of Tiarah Poyau (22) who had been shot point blank range for declining the advances of a man at J’Ouvert. Then I read about a lady called Asami Nagakiya had been strangled in costume in Trinidad Port of Spain and the Mayor released a statement saying maybe if she wasn’t wearing her costume, that would not have happened to her. For me, that got me thinking what carnival means to me and the fact that I’ve found home there, but what that means to occupy that space as a woman and being the person that continues tradition and carnival that was birthed from oppression but sometimes there’s that doubling down of oppression, when it’s occupied by women. It got me thinking about how black women are treated in the spaces that they pioneer. And, how we can preserve the integrity of something. I love carnival. It’s such a big part of my life but I feel that a lot of people who celebrate carnival, and I’m guilty of it myself, forget where carnival comes from and forget what’s at the core of it. Why it happens and why it’s vital and why we should hold on to it for dear life and respect it.

SAJ: Tell us about some of your carnival experiences – good and bad.

YJ: My mum worked at Avenues Youth Club on Harrow Road and worked there for 15 years. It became a big part of my growing up. They had a float, so I’d always be there with her, designing our costumes and my mum used to sell t-shirts, as well. So, the night before carnival we used to be all in the kitchen screen-printing and tie-dying t-shirts, and I’d get to customise my Levi’s and my belly tops. It was fun. It was a big part of my upbringing. We went to the Caribbean for most summers as children (my mum is from Dominica and Jamaica and my dad is from St Vincent) but Dominica is where we had a family home and the island that I’m most familiar with. But we always structured our holidays so that even if we landed at Gatwick in the morning, we’d be at carnival by the afternoon. We went hard. I just associated carnival with family and food and fun. It just felt like a safety net – particularly as a child. I felt like I was under the protection of adults and then a big rite of passage in my family is when you’re old enough to go to carnival on your own. And that’s a different experience as you’re told that if someone does this to you, do this, if someone does that to you, go there, if you see this, walk away… You become aware of the responsibility you have for yourself when you’re in that space.

I believe that women are at the core of carnival.

Growing up I also became aware of how during carnival, people develop heightened versions of themselves and how you can be free and be loose but like I also struggle with the language of consent that exists in carnival that’s kind of unspoken and even though it’s unspoken, it’s important and it exists. That language is that you can have a dance and you can enjoy the closeness of carnival because it’s millions of people all pouring whatever they’ve been carrying all year, into these streets, and it’s feelings, it’s touch, it’s colour, but then there’s also that dance finishing and you being able to walk off and get on with the rest of your day. That should be how it happens. For people who know and respect the culture and go there with integrity it does end that way. But in various instances, it doesn’t. I’ve been in situations personally where guys have grabbed me or have asked me for a dance and I’ve said no, and they’ve asked me why. These interactions can be volatile – it’s tricky because it’s a space where everyone feels quite charged. I feel protective of carnival.

Every year it feels like it’s being dangled on a finer thread and my instint is to want to take it and hold it and hold it close to me but I think it feels untrue to not interrogate the space and some of what happens here. I don’t want to localise it and make it seem like it only happens at carnival but it’s behaviour that transposed to any context. It can be in Glastonbury; it can be at a festival somewhere, there’s something about spaces where women are not wearing lots of clothing and are dancing and are free and being themselves and how that’s contained or compromised by being around others.

Rehearsals. copyright: Helen Murray

SAJ: How do you feel carnival has changed over the years? I used to go religiously every year but then I stopped because I felt like it just wasn’t the same. I feel like it’s a very different carnival to how it used to be.

YJ: Yeh, if you look at west London and where carnival sits within the political landscape of London, west London is a place where the disparity between rich and poor are visible. Literally. Even carnival taking place in the shadow of Grenfell Tower, that’s the year that this play is set in, you just look at these plush houses and the fact that the cladding was actually so the building looked less offensive. If you think about the area and that being an area that’s very Caribbean, and very working class and gentrification has been quite rapid. White girls in string vests and Lily Allen have become synonymous with what carnival is and people will come down and wear Rasta hats and eat things that are labelled jerk but aren’t. It’s just not what it’s about.

I find that frustrating. You hear about parties that are happening within carnival where people have to be on guest lists and it’s like, how does that work? It’s a street party. You can go wherever you want. I think that the heart, the community, the Caribbean-ness of Carnival and that pride – it exists but it’s just fighting against so much more to continue existing. It’s still there but I just feel like so much is being done to homogenise that space and make it something that everyone can feel they have a stake in when it’s like, no you’re all invited but it’s our party for a reason.

What is the connection between carnival and womanhood?

YJ: I believe that women are at the core of carnival. They are in many ways, we are the spectacle, the innovators, the designers, the entrepreneurs, the purveyors and the continuers of the tradition. The are the bassline of carnival. It wouldn’t exist without them. Which is why it feels so important to me that carnival is protected and revered within that space. I want people to come and see this performance and know these girls and feel like, if they can exist on stage then why can’t i? And be like, my story has value and there’s does. It’s very personal and it’s very political but it can be theatrical.

SAJ: Why should readers come and see J’Ouvert?

YJ: It’s funny, it’s honest, it feels like an invitation to have a conversation we haven’t had in this way before and carnival is a space that we’re all so familiar with and lots of us love it in so many ways. We take it for granted and don’t interrogate or investigate and I think it would be nice to have a space where we can do that. The play is just as joyous as it is angry, and it would be great for us to just have this shared human experience and all sit under one roof and feel those things together.