S I Martin – interview

Black Georgians, Black Cultural Archives

As a self-confessed “eighteenth century nerd” S. I. Martin is in his element at the current Black Cultural Archives exhibition. Black Georgians: The Shock of the Familiar transports visitors to a bygone age. An era of bustling dockyards, society balls and political rallies. These prominent historical scenes are ingrained in the British consciousness. But they omit one key feature of Georgian society. The presence of black people. In fact, it is estimated that by the end of the Georgian reign, there were at least 15,000 people of African-Caribbean origin in the UK.

What this exhibition is about is introducing the fact of black Georgians. Because in doing that we’re pushing the boundaries of popular black history back from 1948 with the Empire Windrush and establishing that there was a black community before

As author and historian, Martin explains: “There were approximately 10,000 black people in London at this time, so 3 per cent of the London population. What this exhibition is about is introducing the fact of black Georgians. Because in doing that we’re pushing the boundaries of popular black history back from 1948 with the Empire Windrush and establishing that there was a black community before.”

As an historian, Martin specialises in black British history. Throughout our interview, his skills as a lecturer both in London schools and as a tour guide are obvious. I feel privileged as he takes me on a detailed private tour of the exhibition. A particularly cogent print depicts a classic Georgian parlour scene, full of gentile ladies in bonnets. I do a double take when Martin points out the creole figure amidst the corseted throng.

“In this image, a gentleman has advertised for a bride. You can see the creole lady there, her father would have been a plantation owner and her mother would have been an enslaved person. You can see she’s wealthy, someone whose assets a gentleman would like to possess. She’s a stock character in this period. You see her as Miss Swartz in Thackeray’s Vanity Fair.”

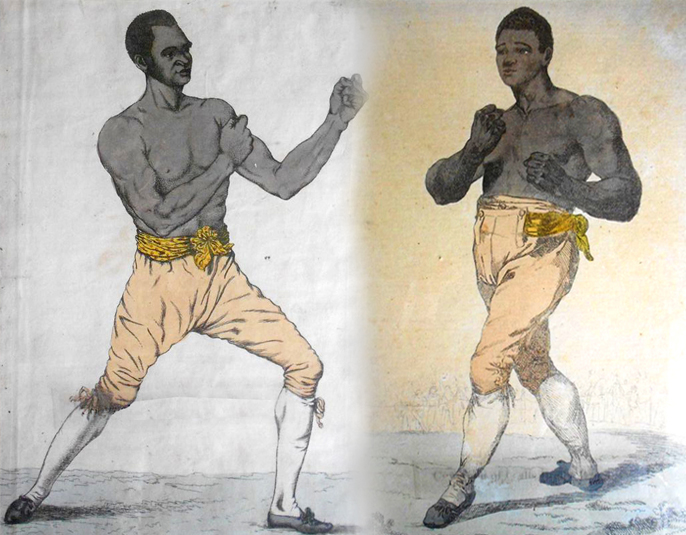

The exhibition covers the period from the coronation of George I in 1714, until 1833 when the Slavery Abolition Act was passed. The vast array of portraits, posters, newspaper clippings and legal transcripts create a vivid impression of the Georgian era. The majority of incredible prints and portraits are on loan from private collector, Leslie Braine-Ikome. With his encyclopaedic knowledge, Martin talks me through each piece. The famous portrait of aristocrat, Dido Elizabeth Belle. An advertisement for a boxing match featuring African American boxer, Bill Richmond. A Cruickshank cartoon of ‘King of beggars,’ peg-legged Billy Waters. Such familiar images with unfamiliar faces demonstrate that black people were present in every echelon of Georgian society.

Martin elaborates: “People were working in a majority of roles. Some were enslaved, working as domestic servants, but you had a huge number of seamen and soldiers. Then you get people who’d been born here generationally already by the 1750s. Then you had an even smaller set that were sent here for education or for business. These were the sons and daughters of either African leaders of African cultures, who were sending their children over here to solidify business agreements or for education.”

This small privileged set inspired Martin’s two children’s novels, Jupiter Williams and the sequel Jupiter Amidships. This duology tells the story of a wealthy young boy from Sierra Leone, sent to the African Academy in 1800. Martin explains that it was not only African leaders who sent their children abroad for their education. It was also known for plantation owners to send their illegitimate favourites to Britain. Rather like a child in a sweet shop, Martin excitedly flits between exhibits to back up each statement. Unnecessarily apologising “I’m sorry, I’m just jumping around. I could ramble forever.” In this case he shows me documentation regarding Nathaniel Wells. This magistrate and landowner was born to a Welsh merchant and enslaved plantation worker. Upon inheriting a vast fortune and estate (including his own mother) he went on to become Britain’s first black High Sheriff.

An especially creative installation is the Unfinished Conversations exhibit, which Martin explains “Focuses upon literature as a revolution.” The display includes extracts and audio transcripts from poet Phyllis Wheatley and abolitionist Olaudah Equiano. It also features one of Martin’s favourite figures “Mr. Blood and Fire, Robert Wedderbun.” “You have this first slew of black writers in English, who are publishing here in Britain. The first time a white British readership is experiencing black thoughts. This had a definite impact on the abolitionist movement.”

Martin has a long standing relationship with the Black Cultural Archives. Having previously worked as their learning manager, he is still very much involved with their educational programmes. In fact after our interview he gives a lecture on Charles Ignatius Sancho as part of the BCA’s free lunchtime talks. As curator and researcher for the exhibition, Martin has gone to great lengths to demonstrate the breadth of black experience during this epoch. As well as verifying the black Georgian presence, Martin reveals another motivation for the exhibition.

“This period holds up so many parallels to our own. We see discussions on issues of migration and of national identity. We see black people in the church, we have notions of repatriations and we see some squeakiness around mixed marriage. Often late 20th and early 21st century people have this idea that history starts with their birth. They have no sense of chronology, WHAT SO EVER. There’s that feeling that these generations are the first to talk about certain types of racism, certain types of discrimination, certain types of culture. But all of these things are parts of debates which have occurred and started a least two hundred years previously.”

My VIP tour of the BCA’s exhibition was a total revelation. It’s not often one gets a private viewing with an acclaimed historian and I feel genuinely enlightened. As part of its mission to celebrate and preserve black British history, the Black Cultural Archives has delved into the distant past. Effectively bringing the hidden Georgian demographic out of the shadows.

As Martin summarises: “It’s there in all aspects of the culture. It’s there in the newspapers, it’s there in the literature and the portraiture. So the really twisted thing is, why is this subject not spoken about? Essentially, I think it’s because the mainstream British historians just didn’t care about it. It wasn’t overtly hostile, they just had no connection to it. But in order to understand the world we live in now, we have to look to the past and realise that black history and British history are unequivocally intertwined.”

Info: Black Georgians: The Shock of the Familiar exhibition (see listing) is at the Black Cultural Archives in Brixton, London until April 9, 2016 / Find out more